- “I love coffee.”

- “I hate coffee.”

Requirements

Before starting, ensure you have the following packages installed:Setup

Start by setting up LangWatch to monitor your RAG application:Generating Synthetic Data

In this section, we’ll generate synthetic data to simulate a real-world scenario. We’ll mimic Ramp’s successful approach to fine-tuning embeddings for transaction categorization. Following their case study, we’ll create a dataset of transactions objects with associated categories. I’ve pre-defined some categories and stored them in data/categories.json. Let’s load them first and see what they look like.- Merchant name

- Merchant category (MCC)

- Department name

- Location

- Amount

- Memo

- Spend program name

- Trip name (if applicable)

Setting up a Vector Database

Let’s set up a vector database to store our embeddings of categories.Parametrizing our Retrieval Pipeline

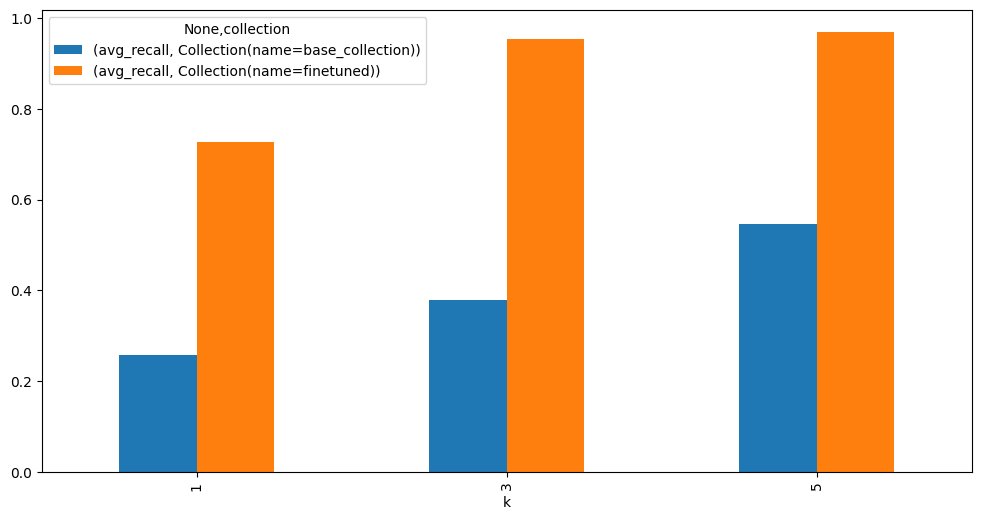

The key to running quick experiments is to parametrize the retrieval pipeline. This makes it easy to swap different retrieval methods as your RAG system evolves. Let’s start by defining the metrics we want to track. Recall measures how many of the total relevant items we managed to find. If there are 20 relevant documents in your dataset but you only retrieve 10 of them, that’s 50% recall. Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) measures how high the first relevant document appears in your results. If the first relevant document is at position 3, the MRR is 1/3.Fine-tune embedding models

Moving on, we’ll fine-tune a small open-source embedding model using just 256 synthetic examples. It’s a small set for the sake of speed, but in real projects, you’ll want much bigger private datasets. The more data you have, the better your model will understand the details that general models usually miss. One big reason to fine-tune open-source models is cost. After training, you can run them on your own hardware without worrying about per-query charges. If you’re handling a lot of traffic, this saves a lot of money fast. We’ll be using sentence-transformers — it’s easy to train, plays nicely with Hugging Face, and has plenty of community examples if you get stuck. Let’s first transform our data in the format that sentence-transformer expects it.

Comparison between base and finetuned models